It's been quite dead on my blog since the last post on the tales of creative writing, and that's because I have been busy in London's big library - so to celebrate the end of the 2025, let's explore the Secret Maps exhibition together and bring the mysteries of mapping alive...

The Secret Maps Exhibition

So, as is usual in blogposts about events, let's talk about what this exhibition is all about. So, Secret Maps is an exhibition that explores mapping and the theme of secrecy and privacy, ranging from 14th century ideas to the present day, taking place at the British Library from the 24th of October 2025 to the 18th of January 2026.

The map curators at the Library had a very tough task over the previous three years in preparing the exhibition for display; choosing the right themes for the exhibition and having to meticulously pick out 100 of the most relevant items from the Library's extensive map collection (4.3 million maps to be precise), along with contacting other heritage institutions and seeing who will offer to loan out their items for display.

Alongside the exhibition itself, the Library also published a book about secret mapping (which also contain maps that were considered for the exhibition, but didn't make the cut), along with a series of events featuring a number of well-respected geographers and academic researchers, which we will get to later on in this post. Without further ado, let's get to my experiences of visiting the exhibition, which took place on the 25th of October.

As soon as I got down the stairs from where the tickets were checked, it was clear that I was going to have a lot of fun attending the exhibition, even before I managed to get to the main exhibition space. starting off with an Ordnance Survey aerial shot over an airbase in Ayrshire that was obfuscated from prying eyes, as seen here:

Moving on just slightly down the hallway from the secret Ayrshire maps, I noticed this television screen that was playing a video about the Reporters Without Borders project "The Uncensored Library", which just goes to show that Minecraft is still accessible to people, even those living in the world's most censored countries. The YouTube video below gives more of an overview into what this Minecraft map is all about:

After having a sneak peek into the inside of the Kowloon Walled City and then progressing out into the main exhibition space, I found it very fascinating to see how maps can play a role in excluding different cultures around the world in order to exploit resources or promote political agendas - such as the AA maps of apartheid South Africa only featuring Afrikaner areas of Johannesburg, or James Cook's maps of New Zealand focusing on European colonisation, as opposed to exploring the needs and desires of the indigenous Maori population.

Moving to World War battles, I have to say that I was quite gobsmacked by the amount of effort that both sides took to falsify maps - ripping stuff out of run-of-the-mill tourist guides and manipulating details for battle purposes (something we would get to see more of in James Cheshire's talk much later on), as well as messing around with different classification levels over the course of the war. Other maps were printed using different colours to avoid detection by enemies, such as this map of Burma in 1943, coloured in orange:

Some military officials even managed to come up with astonishingly devious ways to display maps, such as the use of fashion in this mannequin display containing World War escape maps in them:

But on the other hand, what I have also learned is that maps can be useful for creating imaginative stories and useful discussions on political issues of the day - addressing climate change and its impacts in the Amazon, as well as encouraging positive interfaith dialogue (the latter topic being something that I would get to see more of at an interfaith marriage conference that I attended at the University of Suffolk, about two-and-a-half weeks after going to the exhibition).

The exhibition also posed questions as to how much detail should be included in maps due to privacy concerns - such as Taylor Swift's private jet activity no longer being allowed to be shared live out of concerns that stalkers will use that information to try to find out where she is, as well as the layouts of secret military bases being shared on the fitness tracking app Strava, creating concerns about the data being useful to adversaries in planning their attacks on such installations.

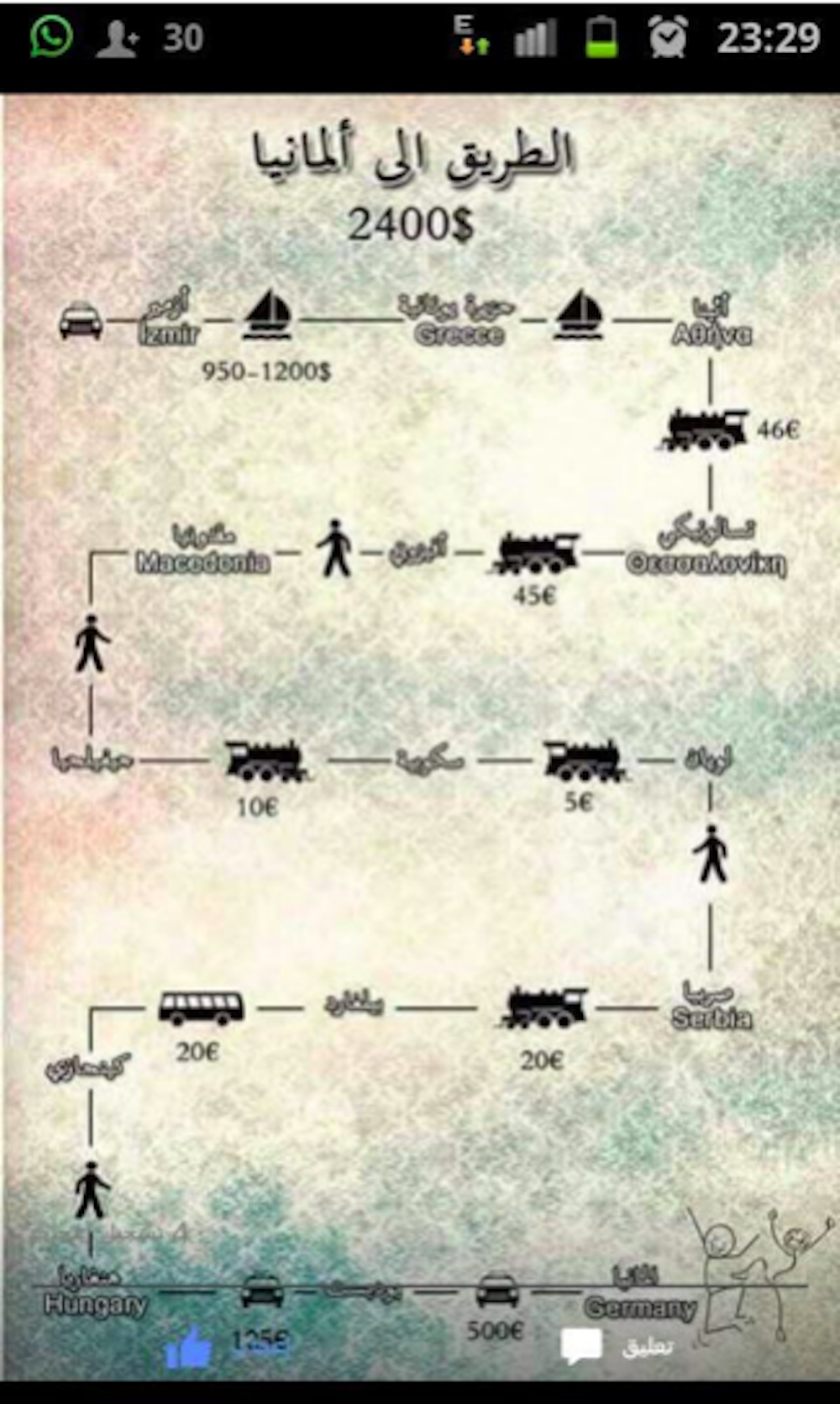

In contrast, secret maps can also be hidden away in encrypted communication groups that only a handful of people can access, such as the Syrian refugees' guide on how to get from Turkey to Germany and the costs involved in each leg, posted on an encrypted WhatsApp group in 2015 (brought to you by researchers at the Open University):

To conclude the exhibition, we were then treated to a moving map of planet Earth, which just goes to show that there are a lot of hidden things going on behind all of the country labels, terrains and placename holders:

Mapping Secrecy with Prof Jerry Brotton (25th October)

Now, before we start this section, let's take the time to explain who is Jerry. So, Professor Jerry Brotton is a respected historian and an academic at QMUL, researching a wide range of historical maps, trade routes and other associated literature, and has appeared on many BBC radio shows and television programmes, most notably the programme on Maps: Power, Plunder and Possession. Without further ado, let's get to the actual talk.

So, after going through the introductions to the event and hearing him share the joy about seeing the exhibition being advertised across the Tube network (and even joking about wanting to ask for the adverts to be taken down), it was time to get to the "paradox" of mapping secrecy, starting with some of the most iconic military maps out there - the 1916 map of the Battle of Somme, the 1944 D-Day battle map of Normandy, where the military was playing around with different levels of classification to deceive the German forces, and the 1981 map of the closed city of Magnitogorsk, which was doctored to wipe out the industrial areas of the city.

At one point, just to prove the point of maps not being entirely accurate, we even got to have some fun around map-related fiction stories, starting with Lewis Carroll's story and the idea of "six inches to the mile" turning into making "a map of the country" on the scale of "a mile to the mile" (an idea that received a lot of backlash), followed by a more mellow depiction of mapping in Jorge Borges' "On Exactitude in Science", which for me struck as a textbook example of why maps always come with decisions on what is in them and what is left out.

Things got even funnier from there - there was this photo of Earth taken on Apollo 17 in 1972, which turned out to be originally taken with south oriented on the top and then flipped the other way round, followed by some treasure exploring, with Hack's drawing of Ireland from 1694 (the Admiralty being impressed with his work) inspiring Stevenson's story on Treasure Island.

After Jerry did some explaining around the Secretum Secretorum, which turned out to be a fake manuscript that was actually written in the 8th century, we then travelled through the galaxy of cartography once more - the voyage of the Moluccas in the 1525 "Salviati Planisphere" and the Pacific Ocean appearing smaller than it is, Saxton's defence maps obfuscated as county atlases, Haci Ahmet's wood engravings that were seized before any hope of reproduction, Cassini's state-sponsored map of France built using trigonometry, and ending on the digital elements, and the concept of "blue marble to the blue dot" indicating the shrinking world that we now live in.

The question period after the talk contained themes so spectacular that they deserve their own write-up analysis, in particular the question about opening up secret maps to include the realms of astronomy - I thought that the question evoked some very strong feelings and feedback about how the exhibition could have been run differently, especially as maps from non-European cultures factor in astrological and other space-related features. The other theme talked about in the question was about creating maps that fit around the context of commercial viability, in the following two questions about "peeling the onion", and who gets to pay the price when Google doesn't tell the truth and doesn't include specific locations on their maps.

And if you want to find out more about Jerry's mapping secrecy story, the British Library have recorded the session that I have been to, so do feel free to go and check out this video here:

With the main talk out of the way, we got round to having two episodes of "What's Your Map" being recorded live, firstly starting off with Professor Nicholas Crane, the author of the "two degrees west" books, where he documents his journey along the second meridian. The main subject of the talk - James Wyld and how his maps influenced the MoD takeover of the Salisbury Plain, an area still used for military drills to this present day.

But before you can talk about why the MoD acquired the plains, you have to go back to the 19th century - 1872 being an important year in the context of British military history - France and Germany were Britain's enemies, and at the time, Palmerston drew 72 forts in the south of England, which set the scene for a fictional story about the Battle of Dorking, which revolved around foreign powers trying to fight their way through the North Downs in an attempt to take the city of London. Consequently, this led to the Military Manoeuvres Act being passed, which gave the military more powers, and as a result, they ended up setting up 37 camps on the Salisbury Plain, removing the existing livestock and residents that had existed before that. Ultimately, the military campaign was successful, and so over the years, the MoD bought pieces of the plain, one-by-one until they were occupying lands the size of Surrey.

The Salisbury talk led on to the start of the discussion about how Crane's book came to existence, and I found it really interesting that the idea started out with a few conversations with a landscaping artist (the artist found it to be a great idea), and as time went by, it was even more mind-boggling seeing the link between James Wyld and Gerard Mercator come together (a link that is crucial in relation to Nicholas's entry point to the Salisbury Plain, especially as Wyld was using dozens of projections that would have made it impossible to puzzle his maps together), and how understanding the technicalities behind the map projections were important to his expedition. Not to mention that his interactions with the military didn't end at the Plain - the Royal Navy had to take him across the Poole Harbour as he didn't have his own boat, and being escorted some more through RAF Lyneham.

If you want to hear more of Jerry and Nicholas talking about the technicalities of his expedition across the UK, the full talk can be found in this video:

With Nicholas's questions all being taken and answered, we then managed to move on to the second set of podcast guests, featuring the Scout organisation, namely the Chief Scout Dwayne Fields, and Caroline Pantling - focusing on the tales and legacies of the organisation's original founder, Lt Gen Robert Baden-Powell. The podcast started off with some mysterious military mapping (although quite tame compared to the palmistry that we would get to see several weeks down the line), with Baden-Powell's depiction of a fort as a butterfly shape - big guns coming out as massive blobs, machine guns as two tiny dots, field guns and lines leading to their locations within the fortress. And there was even more fun to be had with more military positions being obfuscated behind an image of a leaf. The bottom line - nature has the power to obfuscate maps within them.

What was even more fascinating was that Baden-Powell's knowledge didn't stop with his mapping trickery - upon publishing his spy book and returning to the UK, he would go on to work with a group of young boys to encourage people to use their own imagination as a tool and create their own initiatives, and even publish an entire book on that topic. And the Siege of Mafeking, a few years before, was ever more crucial to the Scout Movement's success.

Another fascinating topic that I came across in the talk (and something which would turn out to be a common theme in the questions later) was when Jerry asked Dwayne about how he carries on Baden-Powell's legacy; Dwayne answered the quesion in that he wants to continue to build on that sense of community, improve quality of life and provide opportunities for the next generation of youth - and more importantly by working to cut down the waiting list of 107,000 people by recruiting more volunteers to provide more capacity for Scouting nationwide.

And speaking of questions, my question on how the Scout organisation can support young people in the context of creative writing and fantasy mapping seemed to be very fascinating indeed - while imagination and fantasy is well within the organisation's reach, the biggest takeaway from the answer to that question was that J.R.R Tolkien was once a Scout, and he used his experience to write a story in The Hobbit about defending a town from the dragons.

And if you want to know more about the history of the Scouts, the recording of this talk can be found in this video:

Mapping the Mysterious (21st November)

Now, before we get to the actual talk, let's talk about this piece of artwork at St Pancras railway station:

To me, there are many meanings behind this work - as foreign tourists step off the Eurostar train and are welcomed into the UK, it could mean taking the time to get to know more about London. And for those coming home, it could mean getting ready to spend some time with loved ones, family, you name it. Enough of the artwork talk, let's get to the mysterious and the paranormal.

So, the talk started off with Travis Elborough giving his account on ley line usage - observing the patterns of landscapes, and after getting started on how the circles of Avebury were depicted as serpents, we got round to the main person of the talk - Alfred Watkins, a man from Herefordshire who created mini cameras called bee meters, famously used in Robert Falcon Scott's expedition to the South Pole in 1910. His previous achievements led on to the start of his expedition in 1921, where he communicated to the Woolhope Club about his idea to draw straight lines in an effort to represent traces of history and link mythological sites together. Four places on the line? Possibly a ley. Five? Definitely a ley.

With Watkins' expedition being successful, ley lines started becoming even more popular in the mid 1930s - Kathrine Maltwood and the Glastonbury Zodiac, Even Stranger and his representation of the Nazca Lines, Aime Michel and UFOs, as well as John Michell and his application of ley lines in relation to dragon temples. And even though current scientific consensus rejects the idea of ley lines, the tradition still goes on to this present day - the geomantic design of the Glastonbury stage, and even the design of the town of Milton Keynes are some of the most prominent examples of present day use of ley lines.

With Travis's talk out of the way, it was time to move on to the next guest speaker, Alison Bashford, the author of "Decoding the Hand", and what really set the tone for that part of the talk was her experience in the Wellcome Library, looking through strange body-looking materials that she didn't quite understand what was going on - opening up the scene to the realms of palmistry. At one point, something strangely familiar appeared on the horizons, when Alison was talking about Lionel Penrose and the link between topography and geography to the concepts of palmistry.

And the link between fantasy mapping and non-cartographic features started becoming even more apparent further on - when I was talking to Alison out in the main hallways of the Knowledge Centre after the talks had ended, I managed to get the impression that the idea of the paranormal being illustrated as a map was also something that was also used in fiction and very much so, in the creation of fantasy worlds.

Having being educated on the elements of palmistry being used to depict secret maps, it was time to move on to the final guest speaker Maxim, where he went on to talk about Korean traditions and their influences on secret mapping - the Baekdu mountain range being seen as a source of energy, the city of Seoul and its plethora of mythological artefacts within its palaces creating energy all around, and creatures being sacred everywhere. And speaking of sacred creatures, one of the highlights of his part of the talk was this picture of the Korean Peninsula depicted as a tiger:

Hidden in Plain Sight: Secrets of a Forgotten Map Library (27th November)

Ah yes, it's the one where we have Professor James Cheshire, a key academic in the UCL geography bowels, on board to talk about his book. His talk started off with how the book came to existence - the experiences of his first visit to the UCL map library - the unassuming corridors turning into an Aladdin's cave of maps that are ready to be pulled out of the drawers to have their stories told, and of course, how that experience evolved into three and a half years of work. On the other hand, the introductions also highlighted the sad reality of university map libraries being wiped from existence, along with the unique treasures contained within the collections.

Brushing the mysteries of the map library aside, the fun of seeing the hidden treasures then really started coming into view - the 1930s land utilisation maps that were coloured in by Scout kids, followed by a map of Plymouth with its naval base removed (needless to say, that the Luftwaffe managed to produce a good copy with the military installations added back in as part of their 1943 guidebooks), and the process of the Allies collecting Nazi cartography material after the end of the war and giving them away to map libraries. And ditto with the North London and Ireland handbooks - buildings, cliffs, sandbanks; perfect ingredients for planning amphibious invasions.

And the German copies didn't stop there - they even ripped out copies from the biggest pioneers of map creation, which happened to be the Soviets - classified sea floor data, the constraints of that secrecy subsequently bypassed by physiographic cartography; a technique that is still used to the present day in illustrating depths of seas.

James eventually went on to end his talk on the story of Alexander Rado, a Hungarian cartographer who has had some pretty interesting ups and downs in his career - starting off small by creating promotional maps for Lufthansa and socialist atlases, then moving to Geneva to run Geopress, before suddenly disappearing from public view for ten years, and re-emerging after the end of Stalin's era to gain international recognition and sympathy for his work.

Moving on to the questions, there was a very diverse range of questions asked by the event audience (13 to be exact) - ranging from diversity of map content from each continent (which happens to be dependent on academic interest within UCL), the power dynamics among female cartographers, as well as my question on how much influence historical mapping has had on contemporary military mapping - describing a shift from the state telling what is going on towards people now having the internet resources to access current war information at their fingertips.

Conclusions

Well, what do I have to say about this exhibition. I have to say that the Secret Maps exhibition has packed a massive punch in terms of enjoyment for me, the British Library doing a very good job in planning the themes of the exhibition; it was really fascinating seeing how maps can be used to deceive opponents in military operations, to obfuscate culture and promote cultural cohesion, as well as the present-day aspects, such as maps being used as an OSINT tool to inform people about political and environmental impacts, and the privacy issues that concern modern-day mapping.

Comments

Post a Comment